CHAPTER IIofPRACTICAL MECHANICS FOR BOYS

|

It is singular, that with the immense variety of tools set forth in the preceding chapter, how few, really, require the art of the workman to grind and sharpen. If we take the lathe, the drilling machine, as well as the shaper, planer, milling machine, and all power-driven tools, they are merely mechanism contrived to handle some small, and, apparently, inconsequential tool, which does the work on the material.

Importance of the Cutting Tool.—But it is this very fact that makes the preparation of that part of the mechanism so important. Here we have a lathe, weighing a thousand pounds, worth hundreds of dollars, concentrating its entire energies on a little bit, weighing eight ounces, and worth less than a dollar. It may thus readily be seen that it is the little bar of metal from which the small tool is made that needs our care and attention.

This is particularly true of the expensive milling machines, where the little saw, if not in perfect order, and not properly set, will not only do improper work, but injure the machine itself. More lathes are ruined from using badly ground tools than from any other cause.

In the whole line of tools which the machinist must take care of daily, there is nothing as important as the lathe cutting-tool, and the knowledge which goes with it to use the proper one.

Let us simplify the inquiry by considering them under the following headings:

1. The grinder.

2. The grinding angle.

The Grinder.—The first mistake the novice will make, is to use the tool on the grinder as though it were necessary to grind it down with a few turns of the wheel. Haste is not conducive to proper sharpening. As the wheel is of emery, corundum or other quickly cutting material, and is always run at a high rate of speed, a great heat is evolved, which is materially increased by pressure.

Pressure is injurious not so much to the wheel as to the tool itself. The moment a tool becomes heated there is danger of destroying the temper, and the edge, being the thinnest, is the most violently affected. Hence it is desirable always to have a receptacle with water handy, into which the tool can be plunged, during the process of grinding down.

Correct Use of Grinder.—Treat the wheel as though it is a friend, and not an enemy. Take advantage of its entire surface. Whenever you go into a machine shop, look at the emery wheel. If you find it worn in creases, and distorted in its circular outline, you can make up your mind that there is some one there who has poor tools, because it is simply out of the question to grind a tool correctly with such a wheel.

Coarse wheels are an abomination for tool work. Use the finest kinds devised for the purpose. They will keep in condition longer, are not so liable to wear unevenly, and will always finish off the edge better than the coarse variety.

Lathe Bits.—All bits made for lathes are modifications of the foregoing types (Figs. 18-23, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23).

As this chapter deals with the sharpening methods only, the reader is referred to the next chapter, which deals with the manner of setting and holding them to do the most effective work.

When it is understood that a cutting tool in a lathe is simply a form of wedge which peels off a definite thickness of metal, the importance of proper grinding and correct position in the lathe can be appreciated.

Roughing Tools.—The most useful is the roughing tool to take off the first cut. As this type of tool is also important, with some modifications, in finishing work, it is given the place of first consideration here.

|

|

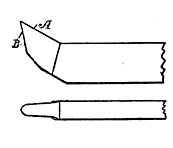

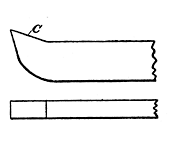

| Fig. 24. Tool for Wrought Iron. | Fig. 25. Tool for Cast Iron. |

Fig. 24 shows side and top views of a tool designed to rough off wrought iron, or a tough quality of steel. You will notice, that what is called the top rake (A) is very pronounced, and, as the point projects considerably above the body of the tool itself, it should, in practice, be set with its cutting point above the center.

The Clearance.—Now, in grinding, the important point is the clearance line (B). As shown in this figure, it has an angle of 10 degrees, so that in placing the tool in the holder it is obvious it cannot be placed very high above the center, particularly when used on small work. The top rake is ground at an angle of 60 degrees from the vertical. The arc of the curved end depends on the kind of lathe and the size of the work.

The tool (Fig. 25), with a straight cutting edge, is the proper one to rough off cast iron. Note that the top rake (C) is 70 degrees, and the clearance 15 degrees.

The Cutting Angle.—Wrought iron, or mild steel, will form a ribbon when the tool wedges its way into the material. Cast iron, on the other hand, owing to its brittleness, will break off into small particles, hence the wedge surface can be put at a more obtuse angle to the work.

In grinding side-cutters the clearance should be at a less angle than 10 degrees, rather than more, and the top rake should also be less; otherwise the tendency will be to draw the tool into the work and swing the tool post around.

Drills.—Holders for grinding twist drills are now furnished at very low prices, and instructions are usually sent with the machines, but a few words may not be amiss for the benefit of those who have not the means to purchase such a machine.

Hand grinding is a difficult thing, for the reason that through carelessness, or inability, both sides of the drill are not ground at the same angle and pitch. As a result the cutting edge of one side will do more work than the other. If the heel angles differ, one side will draw into the work, and the other resist.

|

|

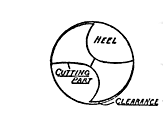

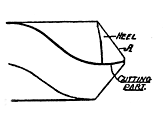

| Fig. 26. End view. | Fig. 27. Side view |

Wrong Grinding.—When such is the case the hole becomes untrue. The sides of the bit will grind into the walls, or the bit will have a tendency to run to one side, and particularly if boring through metal which is uneven in its texture or grain.

Figs. 26 and 27 show end and side views of a bit properly ground. If a bit has been broken off, first grind it off square at the end, and then grind down the angles, so that A is about 15 degrees, and be sure that the heel has sufficient clearance—that is, ground down deeper than the cutting point.

Chisels.—A machine shop should always have a plentiful supply of cold chisels, and a particular kind for each work, to be used for that purpose only. This may seem trivial to the boy, but it is really a most important matter.

Notice the careless and incompetent workman. If chipping or cutting is required, he will grasp the first chisel at hand. It may have a curved end, or be a key-way chisel, or entirely unsuited as to size for the cutting required.

The result is an injured tool, and unsatisfactory results. The rule holds good in this respect as with every other tool in the kit. Use a tool for the purpose it was made for, and for no other. Acquire that habit.

Cold Chisels.—A cold chisel should never be ground to a long, tapering point, like a wood chisel. The proper taper for a wood chisel is 15 degrees, whereas a cold chisel should be 45 degrees. A drifting chisel may have a longer taper than one used for chipping.

It is a good habit, particularly as there are so few tools which require grinding, to commence the day's work by grinding the chisels, and arranging them for business.

System in Work.—Then see to it that the drills are in good shape; and while you are about it, look over the lathe tools. You will find that it is better to do this work at one time, than to go to the emery wheel a dozen times a day while you are engaged on the job.

Adopt a system in your work. Don't take things just as they come along, but form your plans in an orderly way, and you will always know how to take up and finish the work in the most profitable and satisfactory way.

Wrong Use of Tools.—Never use the vise as an anvil. Ordinary and proper use of this tool will insure it for a lifetime, aside from its natural wear. It may be said with safety that a vise will never break if used for the purpose for which it was intended. One blow of a hammer may ruin it.

Furthermore, never use an auxiliary lever to screw up the jaws. If the lever which comes with it is not large enough to set the jaws, you may be sure that the vise is not large enough for your work.

To Chapter III - Setting and Holding Tools

To Table of Contents and Glossary